Trout 101: Species, Habitats, and Angling Tips

Few freshwater fish capture the imagination of anglers quite like trout. These sleek, often colorful members of the salmon family inhabit some of the most pristine waters on earth, from rushing mountain streams to deep, cool lakes. Trout fishing represents more than just a pastime—it’s a connection to nature that has inspired generations of outdoor enthusiasts, writers, and conservationists. Whether you’re a novice angler looking to land your first rainbow or an experienced fisher seeking to expand your knowledge, understanding trout species, their habitats, and effective fishing techniques will enhance your experience on the water. This comprehensive guide explores the fascinating world of trout, providing valuable insights for both beginners and seasoned anglers alike.

The Trout Family: Related Yet Distinct

Trout belong to the Salmonidae family, which includes salmon, char, grayling, and whitefish. While related to salmon, trout have distinctive characteristics that set them apart. Most trout species spend their entire lives in freshwater, unlike salmon, which migrate to the ocean and return to freshwater to spawn. The trout family demonstrates remarkable diversity, with species adapted to various aquatic environments across the Northern Hemisphere. Their close genetic relationship explains many shared characteristics, including their streamlined bodies, adipose fins (the small, fleshy fin between the dorsal and caudal fins), and their tendency to spawn in gravel beds. Understanding these family traits provides a foundation for recognizing the subtle differences between species that can be crucial for identification and fishing success.

Rainbow Trout: The Iconic Game Fish

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) stand as perhaps the most recognizable and widely distributed trout species in the world. Native to the Pacific drainages of North America, rainbows have been successfully introduced to waters on every continent except Antarctica. Their distinctive pink to red lateral stripe gives them their name, though coloration varies widely depending on habitat, diet, and spawning condition. Rainbows are known for their acrobatic fights when hooked, often launching into spectacular aerial displays that thrill anglers. They adapt remarkably well to different environments, from small streams to large lakes, and can grow to impressive sizes—trophy specimens may exceed 20 pounds. The steelhead, a sea-running form of rainbow trout, undertakes ocean migrations similar to salmon before returning to freshwater to spawn, adding another fascinating dimension to this versatile species.

Brown Trout: The Wary European Import

Brown trout (Salmo trutta) originated in Europe and western Asia but have become naturalized across North America since their introduction in the late 1800s. These fish are characterized by their golden-brown coloration, often adorned with black and red spots surrounded by pale halos. Browns have earned a reputation as the most cautious and challenging trout to catch, typically feeding most actively during low-light conditions and retreating to cover during daylight hours. They demonstrate remarkable longevity and growth potential compared to other trout species, with specimens occasionally surpassing 30 pounds in favorable conditions. Brown trout tend to be more piscivorous (fish-eating) than other trout as they mature, developing predatory behaviors that make large streamers and swimming lures particularly effective for targeting trophy specimens.

Brook Trout: The Native Eastern Beauty

Despite their common name, brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) are char, not true trout, though they’re typically grouped with trout in fishing discussions. Native to eastern North America, these fish are distinguished by their dark olive-green bodies covered with distinctive light worm-like markings (vermiculations) on the back and dorsal fin, and red spots surrounded by blue halos along their sides. The brook trout’s fins feature striking white leading edges followed by black and orange coloration. These fish typically inhabit cold, clean waters and are often considered indicators of high-quality aquatic environments. While they rarely grow as large as browns or rainbows, what “brookies” lack in size, they make up for in beauty and their willingness to take flies, making them beloved by anglers seeking wilderness fishing experiences. In fall, spawning males develop intensely colored orange-red bellies that make them among the most visually striking freshwater fish.

Cutthroat Trout: Diverse Western Natives

Cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii) comprises numerous subspecies native to western North America, from coastal rainforests to high mountain streams. Their name derives from the distinctive red or orange slash marks on the underside of their lower jaws. Different subspecies exhibit unique characteristics adapted to their specific ranges, including the Coastal Cutthroat, Westslope Cutthroat, Yellowstone Cutthroat, and several others, many of which are now threatened or endangered due to habitat loss and competition with introduced species. Cutthroats typically display more spotted patterns than rainbows, with spots concentrated toward the tail section. These fish generally prefer colder, cleaner water than other trout species and are often found in high-elevation streams and lakes. Their willingness to rise to dry flies makes them particularly popular among fly fishing enthusiasts seeking authentic western fishing experiences.

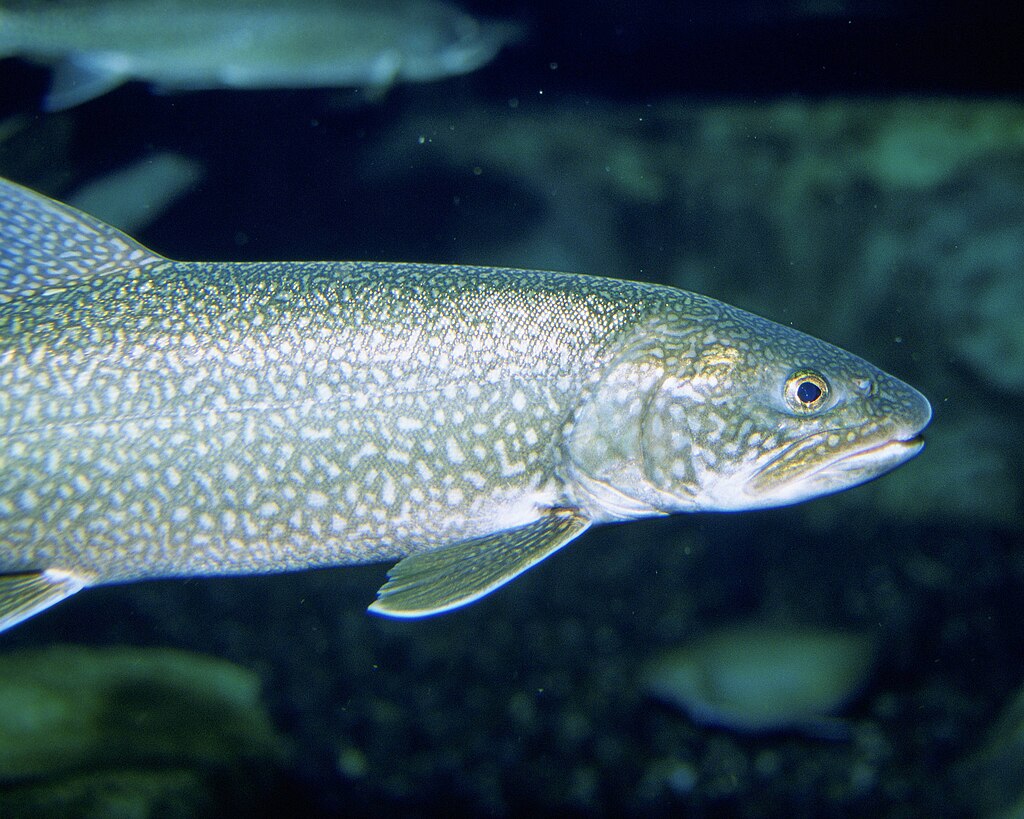

Lake Trout: Denizens of the Deep

Lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush), like brook trout, are technically char rather than true trout. These deep-water predators inhabit cold, oxygen-rich lakes primarily across Canada and the northern United States, including the Great Lakes. Lake trout can live remarkably long lives—some specimens have been aged at over 40 years—and can grow to impressive sizes exceeding 50 pounds. Their bodies feature a dark gray-green background with cream or yellow spots and a deeply forked tail that distinguishes them from other trout species. Unlike most trout that spawn in streams, lake trout typically reproduce over rocky shoals within lakes, broadcasting their eggs during fall spawning runs. Targeting these fish often requires specialized deep-water techniques, including downriggers, wire line, or heavy sinking lines to reach depths where these coldwater specialists reside, particularly during summer months when they may retreat to depths exceeding 100 feet.

Understanding Trout Habitat Requirements

Trout have specific habitat requirements that directly influence their distribution and abundance. The most critical factor is water temperature—most trout species prefer water between 50-65°F (10-18°C), with temperatures above 70°F (21°C) causing stress and potentially death. Dissolved oxygen levels must remain high, which is why trout thrive in moving water or well-circulated lakes with minimal pollution. Cover elements, including undercut banks, submerged logs, deep pools, and overhanging vegetation, provide crucial protection from predators and high water flows. Food availability—primarily aquatic insects, crustaceans, and smaller fish—determines growth rates and population density. Water quality factors like pH balance, absence of pollutants, and appropriate mineral content further define suitable trout habitat. Understanding these requirements helps anglers locate productive waters and contributes to conservation efforts aimed at preserving or restoring prime trout streams and lakes.

Stream Fishing Strategies for Trout

Stream fishing for trout requires an understanding of river hydraulics and fish behavior in moving water. Trout in streams typically position themselves facing upstream in feeding lanes where the current delivers food while requiring minimal energy expenditure. Prime holding spots include the seams between fast and slow water, behind current-breaking rocks, at the heads and tails of pools, and along undercut banks. When approaching a stream, move slowly and stay low to avoid casting shadows or creating vibrations that alert fish to your presence. Work upstream whenever possible, as this approach puts you behind the trout’s field of vision and allows your presentations to flow naturally with the current. Reading water effectively means identifying the subtle surface disturbances that indicate subsurface structure where trout are likely to hold. Match your tackle to the stream size—lighter rods and lines for small creeks, heavier gear for larger rivers—and adjust your presentation based on water clarity and the wariness of the fish.

Lake and Reservoir Tactics

Fishing for trout in stillwaters presents different challenges than stream fishing, requiring anglers to actively search for fish rather than identifying obvious holding areas. In lakes and reservoirs, trout movement patterns are heavily influenced by water temperature, following the thermocline (layer of rapid temperature change) as it shifts seasonally. During spring and fall, trout often cruise shallow areas where food is abundant, making shoreline fishing productive. Summer typically pushes them deeper as surface waters warm, necessitating trolling, deep jigging, or long casts with sinking lines to reach them. Understanding a lake’s contour is crucial—points, drop-offs, underwater springs, and weed bed edges all concentrate trout and their food sources. Weather patterns significantly impact stillwater fishing success, with changing barometric pressure often triggering feeding activity before approaching storms. Wind creates advantages by pushing food organisms toward windward shores and breaking up surface visibility, allowing closer approaches to wary fish.

Seasonal Patterns in Trout Behavior

Trout behavior follows predictable seasonal patterns that savvy anglers can leverage to improve their success. Spring brings heightened activity as water temperatures rise from winter lows, triggering more aggressive feeding after months of relative dormancy. This period often produces the year’s best fishing as trout replenish energy reserves, with midday hours frequently most productive. Summer pushes trout to seek thermal refuge—moving to deeper water in lakes or congregating near cold springs and tributary inflows in streams—with feeding activity shifting to early morning and evening hours. Fall initiates spawning preparations for brook, brown, and lake trout (rainbows typically spawn in spring), with mature fish becoming more territorial and sometimes striking lures out of aggression rather than hunger. Winter slows metabolism dramatically, with feeding windows narrowing to brief midday periods during milder weather. Recognizing these patterns allows anglers to adjust their timing and techniques to match prevailing conditions throughout the year.

Essential Gear for Trout Fishing

Effective trout fishing requires thoughtfully selected gear matched to your fishing environment and target species. Rod selection typically ranges from ultralight to medium-light actions in lengths from 5 to 9 feet, with longer rods providing better line control for stream fishing and shorter models offering accuracy for tight quarters. Reels should have smooth drags capable of protecting light leaders during sudden runs, with line capacity appropriate for your water type. Line choices include monofilament (versatile and forgiving), fluorocarbon (nearly invisible underwater and abrasion-resistant), or fly line with appropriate leaders for fly fishing. Terminal tackle essentials include an assortment of hooks (#8-#16 for most trout fishing), split shot for weight adjustment, strike indicators for drift fishing, and swivels to prevent line twist. Quality polarized sunglasses represent perhaps the most underrated piece of equipment, allowing you to spot fish and underwater structure while reducing eye strain. Finally, appropriate landing gear—nets with fish-friendly rubberized mesh—helps protect trout destined for release.

Fly Fishing Fundamentals for Trout

Fly fishing represents the most traditional approach to trout angling, using artificial flies that imitate insects, crustaceans, and small vertebrates that comprise the trout’s natural diet. The basic fly fishing setup includes a specialized rod, reel, weighted line, leader, and tippet designed to cast nearly weightless flies using the line’s weight rather than the lure’s weight. Dry fly fishing—using patterns that float on the water’s surface—offers the visual thrill of watching a trout rise to take your offering. Nymph fishing employs subsurface patterns that imitate immature aquatic insects and typically accounts for the majority of a trout’s diet. Streamer fishing with larger baitfish imitations targets more aggressive fish and often produces larger specimens. The fly selection process involves “matching the hatch” by observing what insects are active and selecting appropriate imitations in size, shape, and color. While fly fishing has a steeper learning curve than conventional methods, many anglers find its rhythmic casting process and intimate connection with the aquatic environment deeply rewarding.

Conventional Fishing Methods for Trout

Conventional tackle approaches offer highly effective alternatives to fly fishing for trout. Spin fishing utilizes light spinning gear to cast small lures or bait, providing excellent versatility across different water types. Popular lures include spinners (Mepps, Panther Martin, Rooster Tail), spoons (Kastmaster, Little Cleo), and small crankbaits, all of which create flash and vibration that trigger reaction strikes. Bait fishing remains consistently productive, with natural offerings like worms, minnows, salmon eggs, or prepared baits like PowerBait formulated specifically for trout. Drift fishing involves allowing bait to float naturally with the current through likely holding areas, using split shot to maintain appropriate depth. Float fishing (or bobber fishing) suspends bait at a predetermined depth and provides a visual strike indicator when fish bite. Trolling covers water efficiently in lakes by dragging lures behind a moving boat, often incorporating downriggers or lead-core line to reach specific depths. Each method has situational advantages, and versatile anglers often employ multiple techniques depending on conditions.

Catch and Release Best Practices

Ethical catch and release practices ensure trout survive to reproduce and provide future angling opportunities. The process begins before hooking a fish by using appropriate tackle—barbless hooks damage tissue less and extract more easily, while heavier leaders prevent prolonged fights that exhaust fish. Once hooked, land trout quickly rather than playing them to exhaustion, which builds up lactic acid in their muscles and reduces survival rates. Keep fish in the water whenever possible during the unhooking process, as trout gills aren’t designed to function in air. Wet your hands before handling fish to protect their protective slime coating, and support their weight horizontally rather than holding them vertically by the jaw, which can damage internal organs. Revive fish thoroughly before release by holding them gently in the current facing upstream until they swim away under their power. During high water temperature periods (above 68°F/20°C), consider refraining from trout fishing entirely, as fish mortality increases dramatically even with careful release practices.

Conservation Challenges and Trout Management

Trout populations face numerous conservation challenges requiring active management and angler involvement. Habitat degradation from development, agriculture, and resource extraction represents the most pervasive threat, reducing spawning success and carrying capacity through sedimentation, pollution, and riparian destruction. Climate change poses a growing concern as warming water temperatures shrink suitable cold-water habitat, particularly for temperature-sensitive species like bull trout and cutthroat trout. Non-native species introductions have dramatically altered many watersheds, with introduced brown and rainbow trout outcompeting native species in many western waters. Overfishing pressure, particularly for trophy specimens, can skew population dynamics and genetic diversity. Conservation organizations, including Trout Unlimited, work alongside state and federal agencies to address these challenges through habitat restoration projects, advocacy for water protection legislation, and educational initiatives. Anglers contribute through license purchases that fund conservation efforts, participation in citizen science monitoring programs, and practicing responsible fishing that minimizes impact on sensitive populations.

The Cultural and Economic Impact of Trout Fishing

Trout fishing extends far beyond recreational activity to influence culture, literature, and economics worldwide. From Norman Maclean’s “A River Runs Through It” to Ernest Hemingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River,” trout fishing has inspired some of the most celebrated works in American literature, reflecting its deep connection to our understanding of wilderness and self-discovery. Economically, trout fishing generates billions in annual revenue through equipment sales, guide services, lodging, and tourism in fishing destinations. Rural communities near premier trout waters often depend heavily on seasonal angling tourism, creating powerful economic incentives for habitat protection. The conservation ethic cultivated within trout fishing circles has spawned influential environmental movements and legislative protections for watersheds nationwide. Culturally, traditions of trout fishing pass between generations, creating family bonds and connections to place that persist through decades. This multilayered significance explains why trout evoke passionate advocacy among anglers and non-anglers alike, who recognize these fish as indicators of environmental health and symbols of unspoiled natural resources.

Conclusion

Trout fishing offers an unparalleled connection to some of our most pristine natural environments while providing both challenge and reward for anglers of all skill levels. Whether you’re pursuing native brookies in an Appalachian stream,

Post Comment