Sustainable Fishing: What It Really Means

The oceans have long been viewed as an endless bounty, providing humanity with seemingly unlimited seafood. However, modern science has revealed a sobering reality: our marine resources are finite and increasingly threatened by overfishing, habitat destruction, and climate change. Sustainable fishing emerges as a critical approach to balancing humanity’s need for seafood with the ecological health of our oceans. But what does sustainable fishing truly entail beyond the buzzwords and eco-labels? This comprehensive exploration delves into the principles, practices, challenges, and promises of fishing practices that can feed billions while preserving marine ecosystems for generations.

The Crisis in Our Oceans: Why Sustainable Fishing Matters

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that approximately 34.2% of global fish stocks are now fished at biologically unsustainable levels, a dramatic increase from just a few decades ago. This overexploitation threatens marine biodiversity and the livelihoods of the 820 million people who depend on fisheries and aquaculture for income and nutrition. Beyond the direct removal of target species, conventional fishing methods often damage habitats through practices like bottom trawling, which can destroy seafloor ecosystems that took centuries to develop. Additionally, the problem of bycatch—unintentionally caught marine life that’s often discarded dead—claims the lives of millions of non-target fish, sea turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals annually. The situation is increasingly urgent as rising ocean temperatures and acidification from climate change place additional stress on already vulnerable marine populations.

Defining Sustainable Fishing: Core Principles

Sustainable fishing fundamentally means harvesting fish in ways that maintain healthy populations while minimizing environmental damage. At its core lies the principle of managing fish stocks according to their maximum sustainable yield (MSY)—harvesting at rates that allow populations to naturally replenish themselves. This approach requires setting catch limits based on scientific assessments of fish population dynamics rather than short-term economic demands. Ecosystem-based fisheries management expands this view by considering the relationships between species and their environment, acknowledging that removing one species affects the entire ecosystem. Equally important is the principle of minimizing bycatch and habitat destruction through selective fishing gear and protected areas. Lastly, truly sustainable fishing incorporates social responsibility, ensuring fair labor practices and respecting the needs of fishing communities whose cultural identities and economic survival depend on marine resources.

Science-Based Management: The Foundation of Sustainability

Effective fisheries management relies on rigorous scientific data collection and analysis to set appropriate catch limits. Fisheries scientists employ various methods to assess fish populations, including direct surveys, catch data analysis, and increasingly sophisticated computer modeling that accounts for factors ranging from reproduction rates to predator-prey relationships. Regular stock assessments provide crucial information about population trends, allowing managers to adjust quotas accordingly. The concept of “reference points” helps establish thresholds that trigger management actions—for instance, reducing catches when a population falls below a certain level. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) serve as another science-based tool, creating refuges where fish can reproduce undisturbed, often leading to spillover effects that benefit surrounding fisheries. Countries with strong science-based management systems, such as Iceland, New Zealand, and the United States, have successfully rebuilt previously depleted stocks while maintaining commercially viable fishing industries.

Selective Fishing Gear: Technological Solutions

The evolution of fishing gear plays a crucial role in sustainable fishing practices by reducing both bycatch and habitat destruction. Traditional methods like hook-and-line fishing naturally target specific species with minimal environmental impact, while modern innovations bring selectivity to industrial-scale operations. Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawls allow sea turtles to escape nets, saving thousands of these endangered creatures annually. Acoustic pingers on gillnets alert marine mammals to their presence, reducing dolphin and porpoise entanglements by up to 90% in some fisheries. Modified longlines with streamers or set at night have dramatically decreased seabird bycatch, while circle hooks reduce injury to accidentally caught sea turtles and sharks. Even trawling, often criticized for its environmental impact, has seen improvements through raised footropes that minimize seafloor contact and specially designed nets with escape panels that allow undersized fish and non-target species to swim free.

Certification Programs: Market-Based Incentives

Sustainable seafood certification programs leverage consumer purchasing power to reward responsible fishing practices. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), established in 1997, remains the largest global certification system, with its blue eco-label appearing on over 20,000 products in 100+ countries. To achieve MSC certification, fisheries must demonstrate sustainable fish stocks, minimal environmental impact, and effective management. Similarly, the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) certifies responsibly farmed seafood. These programs create market incentives for improvement, as certified products often command premium prices and preferred access to environmentally conscious markets. The economic benefits can be substantial—a 2016 study found that MSC-certified fisheries saw an average price premium of 14% compared to non-certified competitors. Beyond major international programs, regional certification schemes like Naturland (Germany) and Krav (Sweden) address local ecological and cultural contexts, while retailer-led initiatives such as Whole Foods’ seafood rating system further influence the marketplace toward sustainability.

Community-Based Fisheries Management: Local Solutions

Some of the most successful examples of sustainable fishing come from communities that manage their local resources. Traditional ecological knowledge, passed down through generations of fishers, often contains a sophisticated understanding of marine ecosystems that complements scientific approaches. In the Pacific island nation of Fiji, a revival of customary marine tenure systems called “tabu” has established locally-managed marine areas where communities set and enforce their own conservation rules. Similarly, Maine’s lobster fishery has thrived for generations under a system where harbormasters and local fishing communities establish territorial rights and self-impose conservation measures like returning egg-bearing females to the water. The Chilean system of Territorial Use Rights in Fisheries (TURFs) grants fishing cooperatives exclusive access to designated coastal areas for harvesting abalone and other shellfish, creating direct incentives for long-term stewardship. These community-based approaches succeed because they align ecological sustainability with cultural values and economic self-interest, creating powerful motivations for conservation.

Aquaculture’s Role: Beyond Wild Capture

Aquaculture—the farming of aquatic organisms—now provides more than half of all seafood consumed globally and offers potential solutions to overfishing when practiced responsibly. Properly managed fish farms can produce protein efficiently, with some species converting feed to body mass more effectively than terrestrial livestock. Innovations in feed formulation have reduced reliance on wild-caught fish for aquaculture feed, addressing a major sustainability concern. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems demonstrate particular promise by mimicking natural ecosystems—for example, farming seaweed and filter-feeding shellfish alongside finfish, where each species utilizes the waste products of another. Land-based recirculating aquaculture systems minimize pollution and disease risks associated with open-water pens, though they require more energy. However, irresponsible aquaculture practices continue to cause problems through habitat destruction (particularly mangrove clearance for shrimp farms), pollution from excess feed and waste, antibiotic overuse, and the escape of non-native species into local ecosystems.

Traceability and Transparency: Fighting Illegal Fishing

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing undermines sustainable management efforts and costs the global economy an estimated $10-23 billion annually. Combating this problem requires sophisticated traceability systems that track seafood from “boat to plate.” Blockchain technology is emerging as a powerful tool, creating tamper-proof digital records of a fish’s journey through the supply chain. DNA testing provides another verification method, confirming species identity and sometimes even pinpointing geographic origin. Port state measures agreements allow countries to deny port access to vessels suspected of IUU fishing, cutting off their access to markets. Satellite monitoring systems make it increasingly difficult for illegal vessels to operate undetected, with initiatives like Global Fishing Watch providing open-access platforms that allow anyone to track commercial fishing activity worldwide. These transparency mechanisms not only help eliminate illegal fishing but also empower consumers to make informed choices about the seafood they purchase.

Economic Dimensions: The Business Case for Sustainability

Contrary to the perception that sustainable fishing prioritizes environmental concerns at the expense of economic interests, evidence increasingly shows that conservation and profitability can align in the long term. The World Bank estimates that improved management of global fisheries could generate an additional $83 billion annually in economic benefits. This economic case becomes clear when comparing well-managed fisheries to depleted ones—Iceland’s cod fishery recovered from near collapse in the 1980s through strict quotas, and now produces steady catches worth approximately $1 billion annually. Similarly, U.S. fisheries have seen significant economic improvement under science-based management, with the inflation-adjusted value of commercial landings increasing by 54% between 2000 and 2016 while maintaining sustainable harvest levels. The transition period can be challenging, however, as reducing fishing effort in the short term often means immediate economic hardship before stocks recover. Successful approaches typically include assistance programs to help fishers weather the transition, such as vessel buybacks, retraining opportunities, and temporary financial support.

Social Justice: The Human Dimension of Sustainable Fishing

True sustainability encompasses social dimensions alongside ecological and economic considerations. Approximately 40 million people worldwide work directly in fishing, with hundreds of millions more in related industries, many in developing nations where alternatives are limited. Sustainable fishing practices must account for these communities’ rights and needs, ensuring equitable access to resources and decision-making processes. Unfortunately, human rights abuses plague parts of the seafood industry, with investigations revealing forced labor and dangerous working conditions aboard vessels in certain regions. Several major seafood companies have now committed to social responsibility standards, such as the Seafood Task Force’s Code of Conduct. Indigenous fishing rights present another critical dimension, as many native communities maintain deep cultural connections to traditional fishing practices. Court decisions in countries like Canada, New Zealand, and the United States have increasingly recognized indigenous fishing rights, acknowledging both their legal standing and the sustainable practices often embedded in traditional approaches to resource management.

Climate Change: The New Frontier for Sustainable Fishing

Climate change poses unprecedented challenges to sustainable fisheries management through multiple mechanisms. Rising ocean temperatures are already causing fish populations to shift toward cooler waters, often crossing national boundaries and complicating management arrangements. Increasing ocean acidification threatens shellfish by making it harder for them to form shells, while changing current patterns disrupt spawning and migration behaviors. These shifts require adaptive management approaches that can adjust quickly to changing conditions. Some promising strategies include dynamic ocean management, which uses real-time data to establish protected areas that move with target species and oceanographic conditions. Implementing climate-ready fisheries management also means establishing international agreements that anticipate and accommodate shifting fish distributions across political boundaries. Additionally, reducing the carbon footprint of fishing operations through fuel-efficient vessel designs and fishing methods contributes to climate mitigation while often reducing operating costs, creating another win-win scenario for sustainability and profitability.

Consumer Choices: The Power of the Plate

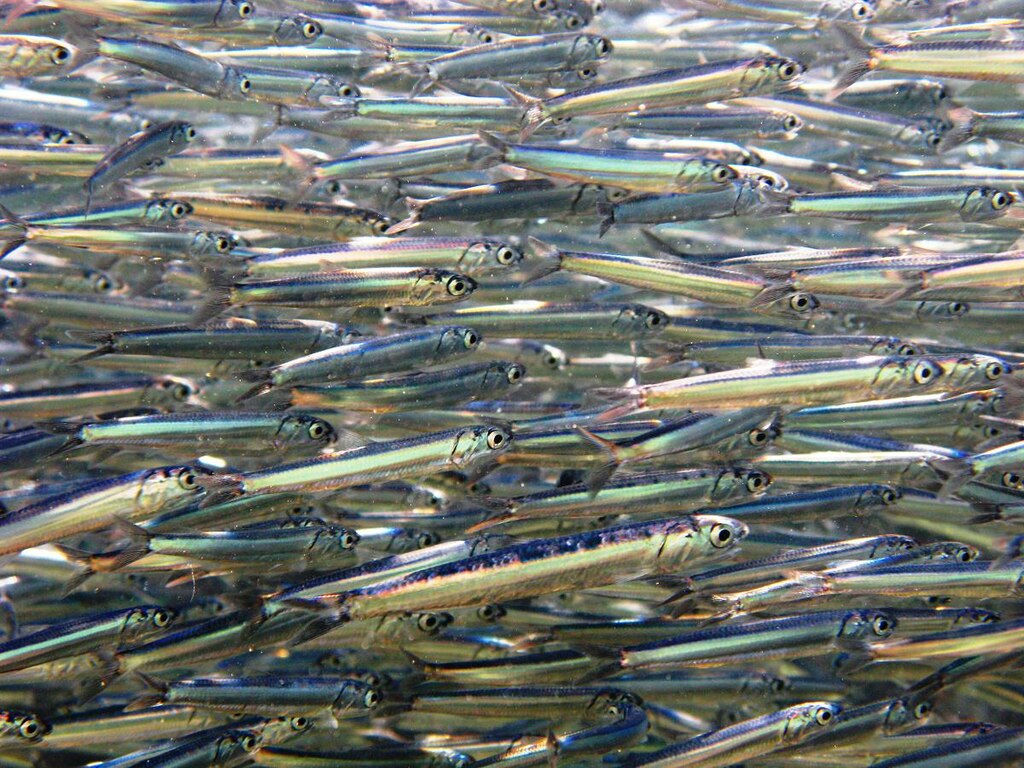

Individual consumers wield significant influence through their seafood purchasing decisions, collectively shaping market demand toward more sustainable options. Seafood guides like the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program offer accessible recommendations categorized as “Best Choice,” “Good Alternative,” or “Avoid,” helping shoppers navigate complex sustainability considerations. Smartphone apps bring this information directly to the point of purchase, allowing consumers to scan barcodes or search for specific species while shopping. Beyond choosing certified sustainable options, diversifying seafood choices can reduce pressure on popular species—many underutilized but abundant species like Atlantic mackerel and Pacific sardines offer excellent nutritional value with lower environmental impacts. The growing farm-to-table movement has expanded to include “dock-to-dish” programs connecting consumers directly with local, sustainable fishers through community-supported fishery (CSF) subscriptions. These direct marketing arrangements typically provide fishers with better prices while giving consumers fresher seafood with transparent sourcing—a model that supports both economic and ecological sustainability.

The Future of Sustainable Fishing: Innovations and Opportunities

Emerging technologies promise to advance sustainable fishing practices in exciting ways. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing observer programs through automated camera systems that can identify species and measure fish with minimal human intervention, enabling comprehensive monitoring at a lower cost. Genetic techniques like environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis allow scientists to detect species’ presence by sampling water for genetic material, providing non-invasive population monitoring. Advances in satellite technology and drone deployment expand surveillance capabilities against illegal fishing, while underwater robotics offers new possibilities for stock assessment without harmful sampling. Beyond technological solutions, innovative policy approaches like fishery improvement projects (FIPs) create structured pathways for fisheries to work incrementally toward sustainability through marketplace incentives. Looking ahead, the concept of “blue food” is gaining traction as part of sustainable food systems, recognizing that aquatic foods often have lower environmental footprints than land-based protein sources. Ultimately, the future of sustainable fishing lies in integrated approaches that combine technological innovation, sound science, market incentives, and community engagement to ensure that seafood remains a vital part of global food security without compromising ocean health.

Conclusion

Sustainable fishing represents one of humanity’s most crucial endeavors—balancing our need for seafood with the health of marine ecosystems that support all life on Earth. While challenges remain substantial, from climate change to illegal fishing, the principles and practices outlined here demonstrate viable paths forward. Success stories from well-managed fisheries around the world prove that with proper science, technology, policy, and community engagement, we can harvest seafood sustainably while preserving ocean biodiversity. The transformation to truly sustainable fishing requires commitment from all stakeholders—fishers, governments, businesses, scientists, and consumers. By making informed choices and supporting responsible practices, each of us contributes to a future where healthy oceans continue to feed humanity while teeming with diverse marine life.

Post Comment